I see that the Star has become interested in Ontario’s rent control legislation after it was discovered that those 32,000 shiny new condos which have sprung up in the downtown core are not covered by rent control. Indeed, it seems that many tenants find themselves facing rent increases which are in excess of the 2.5% limit which is imposed in the case of buildings built prior to 1991.

Not surprisingly, NDP housing critic Cheri Di Novo characterized the exemption as “a loophole that needs to be closed.” Indeed, the Star described the exemption as a “loophole” in its headline. Councilor Adam Vaughan also supports rent control on these units, but told the Star that the controls need to be modeled specifically on the condo market: “It’s a unique market that needs a unique approach.”

Unfortunately the term “loophole” implies that crafty tax lawyers combed through carelessly-worded legislation and found a way to cheat tenants in a manner not intended by the government. In fact, the1991 exemption was a well-publicized measure which was intended to encourage the construction of rental housing.

Presumably everyone can agree that any legislation needs to be fair, however fairness is by definition the balancing of the interests of two or more parties. Would there be greater fairness if modern condos were under the same rent control regime as buildings built prior to 1991?

Prior to the ascent of the Liberal government to Queen’s Park nine years ago the maximum rent increases permitted under rent control were calculated using a formula which took into account the rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index as well as the changing costs of the landlord’s specific inputs… that is, the costs of things like utilities, insurance and property taxes. The result was that the guideline increases were almost always higher than the rate of inflation, which outraged housing advocates. Accordingly, the current Liberal government tossed out the formula and limited rent increases to the rate of inflation… except that under no circumstances could increases be more than 2.5%.

Changes in the Consumer Price Index are typically considered to reflect changes in the “cost of living”. This is misleading inasmuch as the CPI measures the average price change in a hypothetical basket of about 600 goods and services. Most of these are non-essentials, of course, and if the price of these items goes up then people will typically find an alternative or spend their money on some other non-essential. For example, if the cost of air travel goes ballistic a family may opt for a summer road trip to New England rather than a winter getaway to the Caribbean.

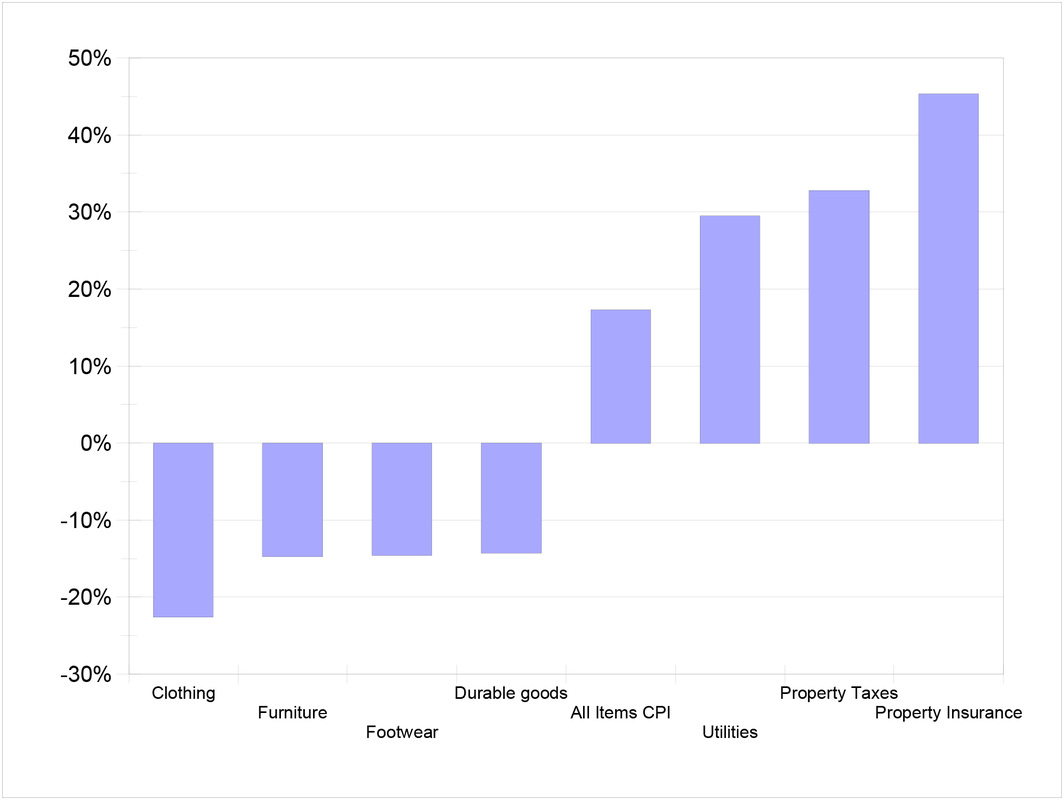

In any case, tying the guideline to the CPI suggests that our legislators have little understanding of the dynamics of inflation. When I moved to Toronto In 1970 I could fill my gas tank for less than it cost to make a five-minute long-distance call to Vancouver. A pair of Clark’s desert boots cost more than two week’s pay, and anyone who travelled by air was considered to belong to “the jet set”. If we examine any decade in the past fifty years we will see that the cost of most manufactured goods has declined relative to the CPI, due to improved manufacturing methods, the shift of manufacturing to low-cost countries, the elimination of import duties and technological innovation. At the same time the cost of everything relating to shelter… property taxes, energy, water, property insurance and construction labour… has increased at rates much higher than the CPI.

As a result homeowners have had to pay higher prices for property taxes, insurance, and water and electricity, however these costs represent only a small portion of a homeowner’s spending and are more than offset by the greater affordability of most goods. So in spite of higher shelter costs the homeowner’s material wealth increases… although budgets need to be rebalanced. Under the existing rent control regime tenants enjoy the benefits of lower prices for goods but are insulated from the higher costs of utilities, taxes and insurance.

Not surprisingly, NDP housing critic Cheri Di Novo characterized the exemption as “a loophole that needs to be closed.” Indeed, the Star described the exemption as a “loophole” in its headline. Councilor Adam Vaughan also supports rent control on these units, but told the Star that the controls need to be modeled specifically on the condo market: “It’s a unique market that needs a unique approach.”

Unfortunately the term “loophole” implies that crafty tax lawyers combed through carelessly-worded legislation and found a way to cheat tenants in a manner not intended by the government. In fact, the1991 exemption was a well-publicized measure which was intended to encourage the construction of rental housing.

Presumably everyone can agree that any legislation needs to be fair, however fairness is by definition the balancing of the interests of two or more parties. Would there be greater fairness if modern condos were under the same rent control regime as buildings built prior to 1991?

Prior to the ascent of the Liberal government to Queen’s Park nine years ago the maximum rent increases permitted under rent control were calculated using a formula which took into account the rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index as well as the changing costs of the landlord’s specific inputs… that is, the costs of things like utilities, insurance and property taxes. The result was that the guideline increases were almost always higher than the rate of inflation, which outraged housing advocates. Accordingly, the current Liberal government tossed out the formula and limited rent increases to the rate of inflation… except that under no circumstances could increases be more than 2.5%.

Changes in the Consumer Price Index are typically considered to reflect changes in the “cost of living”. This is misleading inasmuch as the CPI measures the average price change in a hypothetical basket of about 600 goods and services. Most of these are non-essentials, of course, and if the price of these items goes up then people will typically find an alternative or spend their money on some other non-essential. For example, if the cost of air travel goes ballistic a family may opt for a summer road trip to New England rather than a winter getaway to the Caribbean.

In any case, tying the guideline to the CPI suggests that our legislators have little understanding of the dynamics of inflation. When I moved to Toronto In 1970 I could fill my gas tank for less than it cost to make a five-minute long-distance call to Vancouver. A pair of Clark’s desert boots cost more than two week’s pay, and anyone who travelled by air was considered to belong to “the jet set”. If we examine any decade in the past fifty years we will see that the cost of most manufactured goods has declined relative to the CPI, due to improved manufacturing methods, the shift of manufacturing to low-cost countries, the elimination of import duties and technological innovation. At the same time the cost of everything relating to shelter… property taxes, energy, water, property insurance and construction labour… has increased at rates much higher than the CPI.

As a result homeowners have had to pay higher prices for property taxes, insurance, and water and electricity, however these costs represent only a small portion of a homeowner’s spending and are more than offset by the greater affordability of most goods. So in spite of higher shelter costs the homeowner’s material wealth increases… although budgets need to be rebalanced. Under the existing rent control regime tenants enjoy the benefits of lower prices for goods but are insulated from the higher costs of utilities, taxes and insurance.